What is PEP?

PEP stands for Planet Exploration Project or something. This project’s main idea is to design a vehicle for some kind of habitable/survivable exoplanet/moon. We ended up with a few choices but we landed on Titan.

Titan’s habiltability

Titan has a few pros and cons that make it a somewhat decent place for us to build a habitat in. First of all Titan has a very thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere which shields us from harmful cosmic and solar radiation much more effectively than other places.(Barnett, A. (Ed.). (2025, April 25)) This is a problem especially with other exoplanets, where there is little to no protection from the harsh radiation from space. At its surface the atmospheric pressure is about 60% more than on earth, around the same pressure swimming 15m under the ocean, making the atmospheric pressure less of a concern.

Titan also has abundant lakes and seas of hydrocarbons(mainly methane/ethane), ranging in size from 1km-100km in width. Liquid water isn’t really present on the surface because of the temperatures on Titan(-179°C). This discovery makes Titan the only place we currently know that houses lakes beyond Earth.

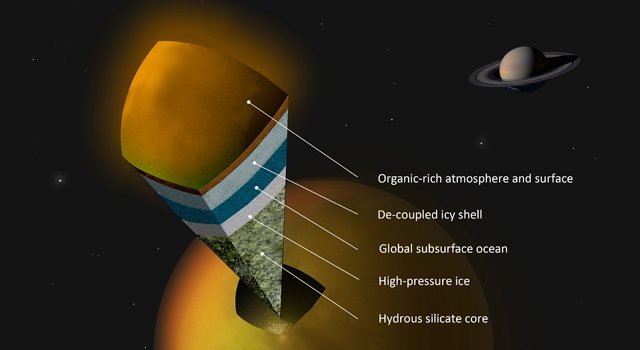

However, beneath the icy crust of Titan radar and gravity data hint at a global underground ocean of liquid water & ammonia. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has given us an insight into the composition of Titan’s layers. As the moon orbited Saturn, researchers saw a large amount of squeezing and stretching, and deduced that if the moon was composed entirely of stiff rock, the gravitational attraction of Saturn would cause bulges, or solid “tides” on the moon only 1 meter in height. Spacecraft data show Saturn creating solid tides approximately 10 meters in height, suggesting that Titan isn’t made entirely of rock. Because Titan’s surface is mostly water ice, scientists infer Titan’s ocean is likely mostly liquid water. (NASA. (2012, June 28).

The reason people think there is also ammonia in the ocean is because it lowers water’s freezing temperature just enough to keep the ocean liquid, along with a few other evidence-backed reasons.

The sunlight on Titan is also minimal, around 1% of Earth’s, making photosynthesis basically impossible. In a detailed study of sunlight on Titan: “Because of Titan’s distance from the sun (10 AU) and the haze in the atmosphere, the maximum level of sunlight on the surface of Titan is about 0.1% that of the overhead sun on Earth’s surface.”(McKay, C. P. P. (2016, February 3)) This means that energy can’t be harvested through photosynthesis but through chemical reactions, maybe through the abundant hydrocarbon resources.

Titan’s Opportunities

Titan presents a surprising amount of opportunities, both scientifically and technologically.

Titan’s atmosphere and surface are full of organic molecules like methane, ethane, etc.— similar to the chemistry that may have preceded life on earth. Studying Titan might help us understand how life would emerge under different conditions, with methane instead of water as a solvent. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22481630/)

The subsurface ocean might provide opportunities for deep sea life just as earth does, and its atmosphere resembles early Earth before oxygen, which might offer insight into the past of our planet, improving our knowledge of atmospheric evolution. (Horst, S. M. (2011, November 18))

Titan has vast amounts of hydrocarbons, which could provide raw materials for fuel or life support, getting us one step closer to people living off the land rather than relying on Earth.

This is a big what if, but if Titan hosts even primitive forms of life, especially ones that rely on liquid methane instead of water, it could completely redefine biology, reshaping our definition of life and how we search for life across the universe.(Caspin-Powell, L. (2018, February 16).

)

Challenges we might face & implications

Having a vehicle operate on Titan is obviously much different than having a vehicle operate here. Here are some requirements and implications that come with having to design a vehicle for Titan:

- Survive the extreme cold and operate reliably while doing so

- Operate not on sunlight— its primary source of power can’t be solar

- Work mostly autonomously— its atmosphere and distance make communications difficuly

- Try to exploit Titan’s unique features— its abundance in hydrocarbon and ice could somehow be used to our advantage

Even though Titan is one of the more promising sites in terms of habitability, it still does have some issues and concerns for us to solve.

One of its challenges we have to overcome is its extremely cold temperatures, at around -179°C. All equipment needs to be insulated like in space and self heating. Even NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly drone has to carry an internal nuclear heat source. For our vehicle that means that batteries/electrical systems are slowed down by the extreme cold. Some materials like plastic might start to become much more brittle than in room temp, and things like rubber are more stiff. This is also why winter tires are less stiff in design than normal tires.

A few solutions to the cold are as follows:

As mentioned before, carrying an internal heat source is a good idea that keep everything inside the vehicle(and the people) at a operational temperature. Insulation materials are also needed. An example could be tungsten, however its density might raise some other concerns. Materials need to be chosen correctly so that they don’t become brittle or stiff. Electronics, other than internal heating also might need to be specifically made to work in extreme cold, or rated to do so.

Another concern is the lack of sunlight. Most space exploration vehicles that are in close proximity to the sun rely on a mix of solar and nuclear energy. On Titan, the amount of sunlight(~1% of Earth’s) limits our energy sources, which means obviously our primary source of energy can’t be solar. We would probably rely on nuclear energy, or attempt to harvest the hydrocarbons that are abundant on the surface. The icy surface OR the liquid ocean underneath also can be used to our advantage. Remember that combustion usually requires a hydrocarbon(abundant) and oxygen. Something like electrolysis could be used to produce H2 and O2 gas, which can be used in combustion— CxHy + (x + y/4)O2 -> xCO2 + (y/2)H2O, but we also need to consider the energy input needed for electrolysis, which is not little by any means.

Its terrain, though full of opportunity is also extremely risky because the surfaces are very slippery, not well mapped and also chemically reactive(methane, ethane might combust).

Here are some potential solutions to the terrain:

For the slippery terrain, there are a few solutions. We can manipulate how our vehicle makes contact with the ground, through things like adding spikes or changing the material. Another interesting solution is using a rotorcraft design, like NASA’s Dragonfly, which is also exploring Titan sometime in 2028. They probably decided on a rotorcraft because of the gravity on Titan(0.14g), and because of its less than ideal terrain. Its terrain is also not very well mapped. Things like LIDAR are a good idea, to precisely map the terrain. Because we are taking 5km trips to a certain site on Titan in the project, it’s a good idea to map the terrain out just to know where the site is. A small drone also could be useful if visibility allows with radar to map the surface across a larger area. The methane and ethane are also a concern, but because the atmosphere is mostly anoxic(free of oxygen), the only combustion will come from the oxygen that we introduce into Titan. Obviously it is still a concern because combustion is so important to our vehicle actually functioning, thus we need to avoid using oxidizers/oxygen in general when near hydrocarbon sources or just ensure we are strictly separated from them.

This might not be a concern when we’re doing the project but Titan is 1.4B km from earth, and signals might take hours for round trip. Its thick atmosphere makes direct radio contact with the ground weak or basically impossible, and it would take around 6-7 years to arrive there in person.

How we know what we know

There are 2 main missions that collected most of the data that lets us draw conclusions about Titan. Here’s a quick summary of the both:

VOYAGER 1 FLYBY(1980)

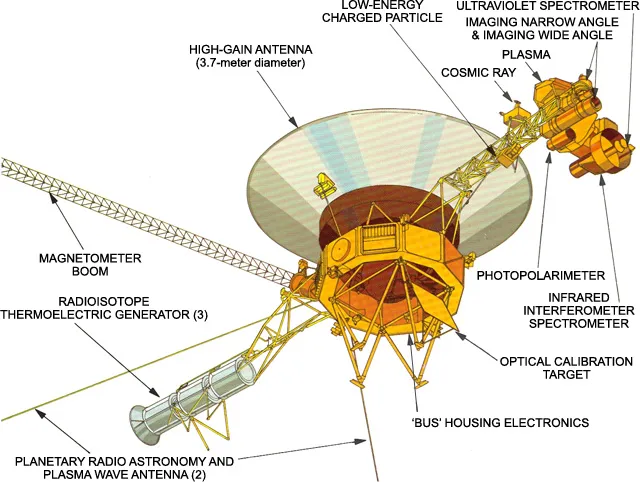

The Voyager 1 had a total of 11 instruments, but only 4 are active currently. Here are the ones that are relevant to the Titan flyby:

- Imaging Science Subsystem(ISS)

- Ultraviolet Spectrometer(UVS)

- Infrared Interfrometer Spectrometer(IRIS)

- Radio Science System(RSS)

Here are the objectives of each instrument(NASA. (2025, April 7)

):

ISS: observe and characterize the atmosphere, and determine wind velocity in the observed regions, etc.

IRIS: measure the abundance of Hydrogen and Helium, etc.

UVS: look for specific colors of UV light that certain compounds & elements emit

RSS: use the radio transmitter to see how Titan’s atmosphere affected radio waves, letting us reconstruct temperature, pressure etc.

This mission mostly concluded that Titan has a thick atmosphere composed of nitrogen(~95%) with methane and trace organics, and that the surface was extremely cold, and its sunlight penetration very little.

CASSINI-HUYGENS MISSION(2004-2017)

This mission was a joint effort, with Cassini orbiting Saturn while Huygens descended onto Titan. This mission revolutionised everything we know about Titan.

Here is a snippet from NASA’s website detailing the instruments used on Cassini:

Cassini’s 12 science instruments were designed to carry out sophisticated scientific studies of Saturn, from collecting data in multiple regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, to studying dust particles, to characterizing Saturn’s plasma environment and magnetosphere.

Optical Remote Sensing

Mounted on the remote sensing pallet, these instruments studied Saturn and its rings and moons in the electromagnetic spectrum.

- Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS)

- Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS)

- Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS)

- Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS)

Fields, Particles and Waves

These instruments studied the dust, plasma and magnetic fields around Saturn. While most didn’t produce actual “pictures,” the information they collected is critical to scientists’ understanding of this rich environment.

- Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS)

- Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA)

- Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS)

- Magnetometer (MAG)

- Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI)

- Radio and Plasma Wave Science (RPWS)

Microwave Remote Sensing

Using radio waves, these instruments mapped atmospheres, determined the mass of moons, collected data on ring particle size, and unveiled the surface of Titan.

This mission found a few key things. It identified liquid methane & ethane lakes near poles, found hydrocarbon deposits, and detected complex organics like HCN, C2H2, C2H6, etc, found prebiotic chemistry similar to early Earth, confirmed the dense nitrogen atmosphere that Voyager 1 found, and found flexing of the surface which hinted at a global subsurface liquid ocean.

The Huygens lander had 6 instruments, and once again here’s another snippet from ESA’s website:

To gather as much science as possible during its historic mission, the Huygens probe was equipped with six experiments.

Aerosol Collector and Pyrolyser (ACP) collected aerosols for chemical-composition analysis. After extension of the sampling device, a pump draws the atmosphere through filters which captured aerosols. Each sampling device could collect about 30 micrograms of material.

Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR) took images and made spectral measurements using sensors covering a wide spectral range. A few hundred metres before impact, the instrument switched on its lamp in order to acquire spectra of the surface material.

Doppler Wind Experiment (DWE) used radio signals to deduce atmospheric properties. The probe drift caused by winds in Titan’s atmosphere induced a measurable Doppler shift in the carrier signal. The swinging motion of the probe beneath its parachute and other radio-signal-perturbing effects, such as atmospheric attenuation, were also detectable from the signal.

Gas Chromatograph and Mass Spectrometer (GCMS) was a versatile gas chemical analyser designed to identify and quantify various atmospheric constituents. It was also equipped with gas samplers which could be filled at high altitude for analysis later in the descent.

Huygens Atmosphere Structure Instrument (HASI) comprised sensors for measuring the physical and electrical properties of the atmosphere and an on-board microphone that sent back sounds from Titan.

Surface Science Package (SSP) was a suite of sensors to determine the physical properties of the surface at the impact site and to provide unique information about its composition. The package included an accelerometer to measure the impact deceleration, and other sensors to measure the index of refraction, temperature, thermal conductivity, heat capacity, speed of sound, and dielectric constant of the (liquid) material at the impact site.

The lander obtained the first images of Titan’s surface plains, with rounded “pebbles” of water ice. It precisely measured the atmosphere and its composition, confirming previous findings(95% N2, 5% CH4, trace ethane, hydrogen cyanide). It also confirmed the surface pressure, the temperature, and evidence of surface liquid methane. It showed the surface was soft and moist, somewhat like wet sand.

A lot of other conclusions were drawn by authoritative summaries and reports made about the mission, like the Icarus “Titan Special Issues” (2006-2015), made of multiple peer-reviewed papers summarising Cassini’s decade of Titan observations, or the Titan from Cassini-Huygens (Coustenis & Tobie, 2019).

AI Use

Citations/References

(Barnett, A. (Ed.). (2025, April 25). Titan: Facts. https://science.nasa.gov/saturn/moons/titan/facts/)

(Horst, S. M. (2011, November 18). Abstract. ABSTRACT. https://scicolloq.gsfc.nasa.gov/Horst.html

)

Leave a Reply to trisonc Cancel reply