Hi everyone, This post is gonna be about the planet exploration project.

If you’ve seen my previous post, then you know what’s going on.

Before we continue, I’d like to disclose that AI (artificial intelligence) was not used in this post.

Introduction / Abstract

The goal of this project was to design and test a vehicle capable of traversing the moon Enceladus through underwater exploration. Given the presence of oceans beneath Enceladus’s icy surface, our team chose to approach the problem from an aquatic perspective and explored the possibility of a submarine-based vehicle.

Our definition statement was: The four astronauts operating the vehicle need to be able to operate and traverse in cold underwater temperatures of −201.67 °C, uneven terrain, maintain stability under high-pressure conditions, and remain energy-efficient so the vehicle can travel at least 10 km on a single energy supply while minimizing environmental impact for future missions.

Testing was intended to evaluate whether a submarine design could realistically achieve basic functionality, including buoyancy control, propulsion, and energy efficiency. The purpose of the test was to determine whether the concept was viable or fundamentally flawed and to identify major design failures early in the process.

Method / Procedure

The final proposed solution was a submarine-style vehicle designed for underwater travel. CAD models were created for the full vehicle as well as for individual systems, including propulsion and buoyancy compartments. A physical prototype was constructed based on these designs.

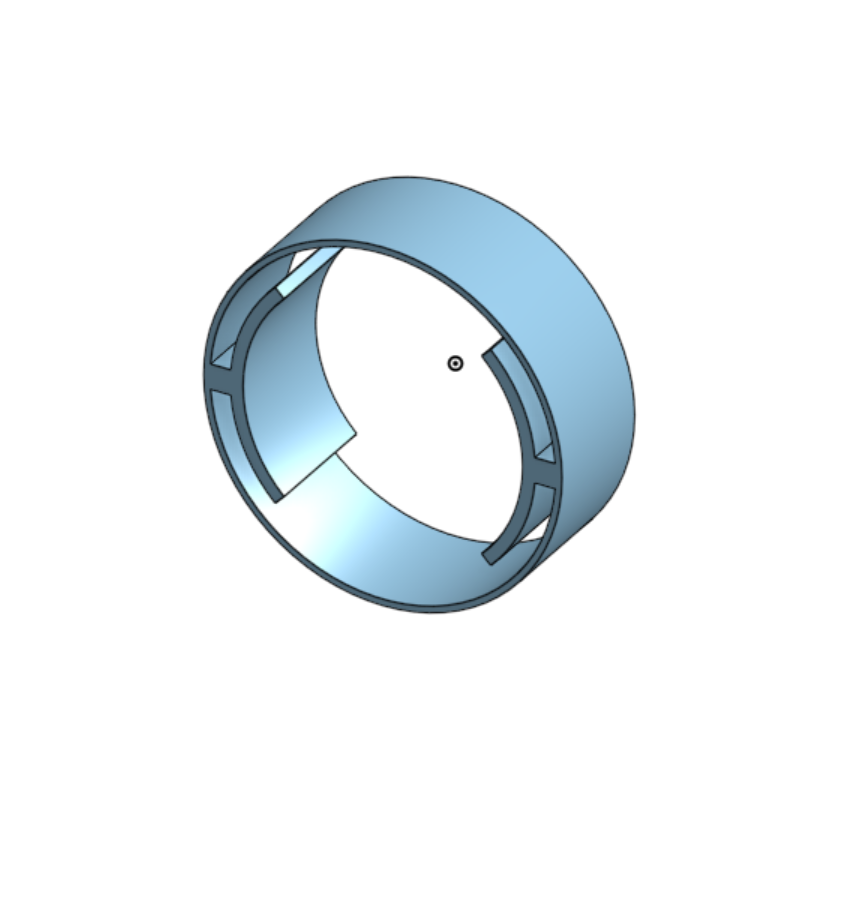

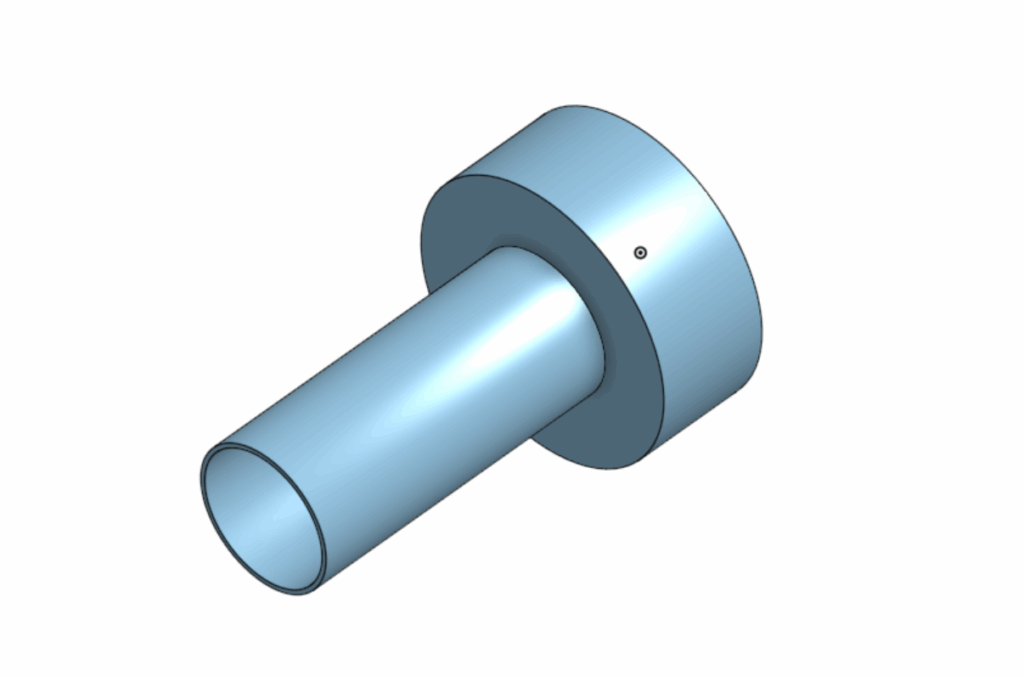

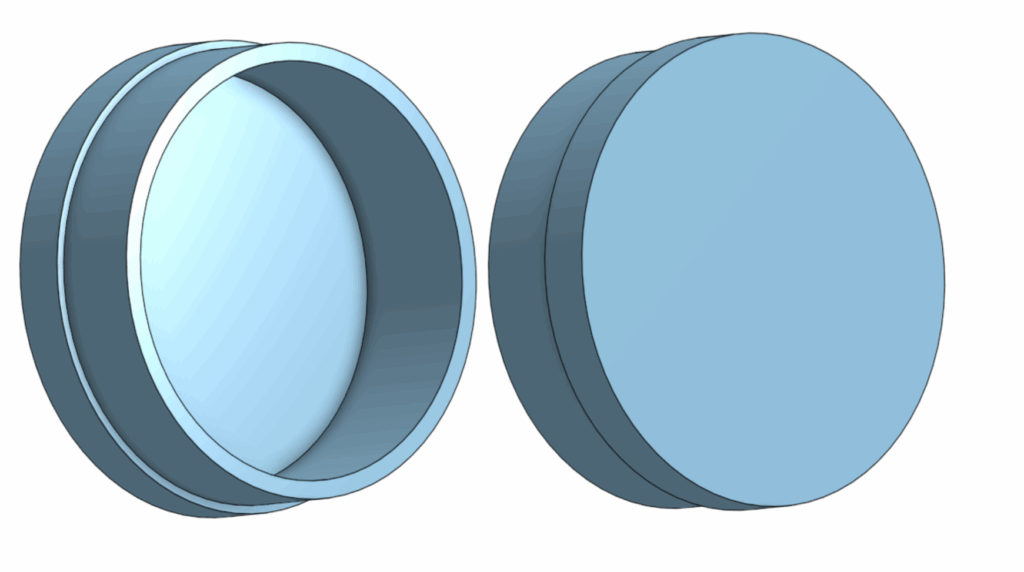

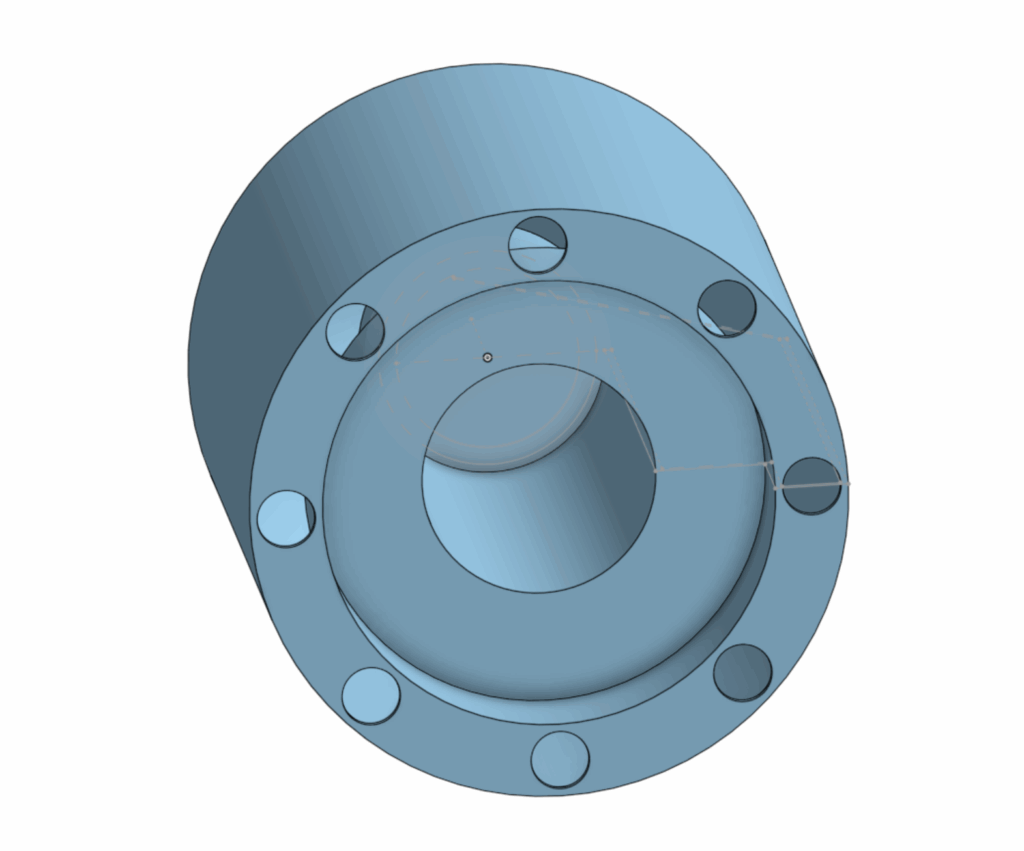

Here are CAD images for the individual parts of the submarine

Motor holster: Designed to hold the motor still as it spun.

Motor housing: A compartment for the motor to sit in, shielding it from the water ballast compartment

Sealant caps: Seals off the internals of the submarine from water

Main Body: this includes the motor housing and the water ballasts.

The testing procedure involved submerging the prototype in water and evaluating buoyancy, movement, and propulsion. The motor was first attached to a magnetic holster system intended to transfer rotational motion to an external propeller. Once powered, the submarine was sealed and placed into the testing environment.

During the build and testing process, numerous failures occurred. Initial tests revealed that the motor did not provide sufficient usable torque and that the magnets were too strong, causing the motor to stall. After changing the magnets, it became clear that internal magnetic friction prevented effective motion transfer to the external propellers. The motor was then replaced, which allowed the propulsion system to rotate, but not in a controlled or usable way.

Buoyancy testing revealed that the submarine was incapable of sinking. In response, a second compartment was added to allow water intake and increase mass. However, this solution was poorly implemented and ultimately ineffective.

Video for first buoyancy test.

Testing / Data

The final test was a complete failure.

From the beginning, the prototype was not test-ready. A basic design oversight; no on/off switch caused the motor to run continuously, making controlled assembly nearly impossible. Attaching the motor and propulsion system became a struggle. When the internal motor was finally secured, the external propeller could not be attached because the motor spun too quickly and the magnetic coupling was far too weak to catch and maintain alignment.

The buoyancy system failed entirely. The ballast compartment was insufficient and did not allow enough water into its compartment to overcome positive buoyancy. As a result, the submarine never submerged and could not perform its intended function.

No meaningful quantitative data was collected. The prototype never achieved propulsion, movement, or submersion. Before any measurements related to speed, energy efficiency, or maneuverability could be taken, the propulsion module detached during the third attachment attempt and broke, ending all further testing.

In summary, the test produced no usable data and demonstrated that the prototype was mechanically unstable, poorly integrated, and not functional enough to validate any aspect of the design.

Analysis

Because the prototype failed to function, no quantitative data was available for formal analysis. No calculations, graphs, or energy efficiency measurements could be produced.

However, the lack of data itself is significant. The failure shows that the design did not meet the requirements for testing. Issues included motor control, ineffective magnetic coupling, buoyancy, and weak structural connections (i.e the propellor). These problems show that the design was conceptually flawed and not ready for real world testing.

As a result, the energy efficiency of the design could not be calculated, as the vehicle never achieved propulsion or sustained motion.

Analysis pt 2

Since our experiment yielded zero results, a hypothetical analysis was conducted using assumed operating conditions.

Based on our hypothetical analysis, the total energy input to the system was estimated to lie in the range of 130–180 J for distance covered. This estimate comes from the assumption that the submarine maintained a constant velocity of 1 meter per second, and that an electrical current of 1 A was supplied to the propulsion circuit from a 6V battery.

An overall system efficiency of 15% was assumed to reflect realistic losses due to electrical, mechanical, and hydrodynamic inefficiencies.

Efficiency = E-useful / E-imput

E-useful is the energy used for propulsion. The useful energy required for the submarine to travel a distance of one meter was calculated to be approximately 9J per meter, which corresponds to 15% of the estimated input energy per meter.

E-useful=Efficiency x E-input

An overall efficiency of 15% represents an exceptionally strong performance for a small-scale underwater propulsion system.

Conclusion / Evaluation

The project did not result in a functional prototype. However, it clearly demonstrated the consequences of inadequate system integration and insufficient testing preparation. The design failed to meet basic operational requirements, including controlled propulsion, buoyancy adjustment, and structural stability.

If the project were to be continued, improvements would include adding a proper motor control system with an on/off switch, eliminating or redesigning the magnetic propulsion coupling and implementing a reliable ballast system with sufficient water capacity.

In its current state, this design would not function in a real Enceladus environment and would fail immediately under extreme temperature and pressure conditions.

Personal Note

I would like to note that I personally did not support the decision to build a submarine. My original proposal was to design a simple rover, which I believed would be significantly more achievable given the time and technical constraints of this project. However, one group member initially suggested the submarine concept in a persistent, joking manner, and the group fully supported pursuing it. As a result, the team committed to a submarine design despite its complexity.

Looking back, this decision directly contributed to the project’s failure. The submarine concept introduced avoidable challenges in buoyancy, propulsion, and sealing that were beyond our team’s capabilities under time constraints.

Leave a Reply