Overview

The Fusion Planetary Exploration Project challenges us to investigate a potential celestial body suitable for inhabitation. The choice that stood out most to us was a famous one of Saturn’s 274 moons, Titan.

One of our primary reasons for choosing Titan is its proximity to the Earth relative to other Earth-like planets/moons. Being 1.2 billion kilometres, and about 6-7 years of continuous space travel away from us, as compared to the thousands of light-years of others, there is a real possibility of human reach extending out to this moon.

Opportunities

Aside from its proximity, Titan’s surface is made primarily of ice, which covers a rocky surface that allows space vehicles to land on. We can find important opportunities in these lands, as well as take inspiration from many of the ISS’s methods of sustaining life. Firstly, we can obtain a sustainable water source through recycling urine. As NASA’s recent report on “Environmental Control & Life Support Systems” suggests, this process is achieved through firstly separating the nutrients found in urine from the waste liquid, before distilling this liquid to capture the remaining, drinkable water that is then stored in a urine brine. Alongside consumable water, this procedure allows us to recover key nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen to be used in fertilizer, which helps us create farms on Titan. This process may be supplemented, especially in emergencies, by melting Titan’s vast icy surface for water.

Due to Titan’s lack of oxygen in its atmosphere, we must make use of the ISS’s invention of electrolysis. As stated by NASA’s recent report, this process uses large plots of solar panels to capture the energy required to decompose water (H2O) into Hydrogen (H) and Oxygen (O) for us to breathe. The supply of water may be found not only in the urine recycling process, but also be kick-started by melting Titan’s unique, icy surface. We can make use of its extensive sheets of ice to obtain the initial water needed to begin water recycling and electrolysis (oxygen creation), rather than mandating the water to be transported from Earth.

Alongside this, Titan has a thick atmosphere made up of methane and nitrogen, which works to provide the moon with a strong greenhouse effect that protects it from radiation. The hundreds of lakes of hydrocarbon composites, as well as rain formed from hydrocarbon clouds, can be used as a sustainable fuel for machinery, and imply the possibility of long-term human habitation. Hydrocarbons are known as highly-effective fuel sources due to their energy density, safety of use, and ease of storage and transportation. Titan’s complex terrains mandate the efficient collection and transportation of Titan’s abundance of raw materials, which Hydrocarbon properties are suitable for.

Because of Titan’s many properties that allow it the ability to support, accommodate, and potentially sustain human life, we believe it to be the most suitable candidate for human inhabitation.

Challenges

Despite these promising opportunities, we must not overlook the significant challenges that oppose human inhabitation on Titan. Currently, the two greatest challenges we face include the extreme cold of the atmosphere and the limitations for mass human population. Firstly, due to its remoteness from the sun, being outside the habitable zone, Titan lacks the necessary heat to allow for unmoderated human activity. The conditions of Titan, often reaching -180°C, prompt us to limit our activities to indoors. Our movement may be significantly limited on Titan due to the requirement of heavy clothing and accessories, which may limit our ability to develop appropriate infrastructures and life-sustaining systems on Titan.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, there are expected limitations for a large human population. The proposed solutions to creating sustainable water and oxygen sources and to creating fertilizers for farms assume their use for small communities. Processes such as electrolysis require large plots of solar panels, which, when combined with the delicate structures used in urine recycling and the requirement for humans to live indoors, limit the possibility of great infrastructural developments over a short period of time. The ISS’s size reflects this limited growth. Although we are free to use far larger lands on Titan, its distance from Earth restricts the efficient shipping of essential materials to build structures that can host larger human populations.

Lastly, Titan’s distance away from Earth, mandating 14-16 years for a round-trip, means that the inhabitants of Titan cannot make emergency contact with Earth. Emergency aid will not reach Titan in time to be serviceable, and difficult situations, such as system failure in urine recycling or electrolysis, that require immediate attention cannot be addressed.

Vehicle Implications

Appropriate vehicle design would need to accommodate the extreme cold temperatures of Titan. Inhabiters will likely be limited to indoor activities or select outdoor ones with spacesuits. Before official habitation, we must set up large plots of solar panels, indoor-suited infrastructures, drills that allow us to dig into Titan’s underground ocean, and functioning life-sustaining systems that work against the temperature.

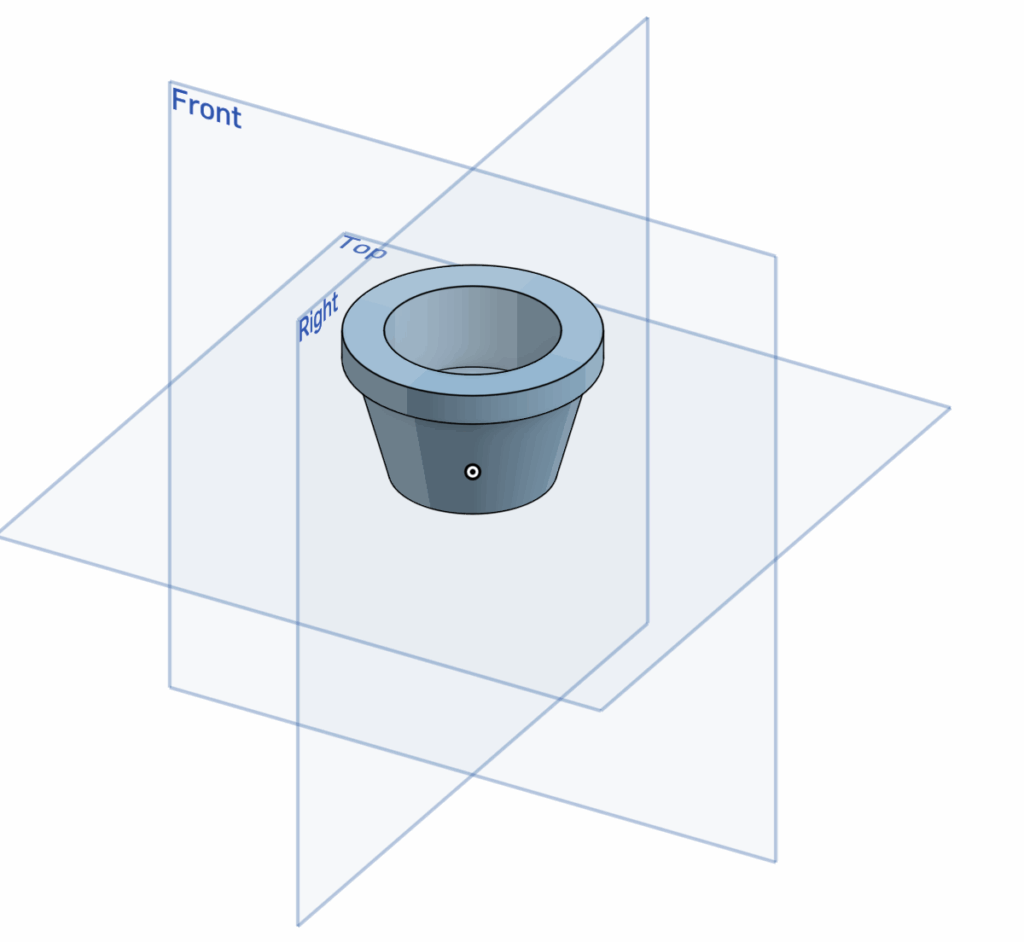

Because of Titan’s lower gravity, at around 1.352 m/s² compared to Earth’s 9.807 m/s², vehicle designs require a way to keep it tight to the ground. This issue should be easily approached, as adding spikes on vehicle treads will allow it to grip Titan’s icy surface, similar to the use of studded tires on a snow bike. An appropriate vehicle for Titan must also be able to withstand the moon’s extreme temperatures and allow for remote control of the vehicle without signals. Due to Titan’s thick atmosphere, blockading radio waves and other forms of electromagnetic radiation, we may need to find a workaround for remote control. Pre-programmed and tested directions can serve as an alternative to remote control, albeit with differing probabilities for success as compared to remote control, based on the situation and use case.

How can we be certain of this information?

Our primary source of knowledge about Titan was found through the “Cassini-Huygens” mission. This mission consisted of two important elements. The “Cassini” was a spacecraft designed to orbit and collect data about Saturn. Attached to it, the “Huygens” was a probe designed to land on its largest moon, Titan. As stated by NASA’s Cassini mission report, the spacecraft and probe’s numerous gravity measurements of Titan revealed the liquid water and ammonia ocean beneath its surface, as well as data for multiple lakes and other bodies of liquid methane and ethane, replenished by rain from hydrocarbon clouds.

The Huygen Probe recorded videos, snapping images, and collecting data on Titan’s atmosphere, including its temperature, pressure, density, and chemical composition (nitrogen-rich) during its 2-hour descent. Upon landing, the probe traversed Titan’s surface for over an hour before running out of battery. Delving into a deeper understanding of the spacecraft and probe’s data collection methods, the Huygen carried many technologies that continuously transmitted information from the probe to the mother “Cassini”.

Firstly, the Huygens Atmospheric Structure Instrument (HASI) used a suite of physical, electrical, and thermal sensors to determine the atmospheric properties of Titan. Accelerometers were used to measure the speed of descent of the probe, which, when combined with the information of its weight and the resistance the probe faced, allowed scientists to understand the density of the atmosphere. This, combined with the Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (GCMS), which was equipped with samplers that tested for the atmosphere’s chemical composition, provided evidence for a Nitrogen-rich atmosphere.

Secondly, the Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR) used a range of imaging observations using several sensors and perspectives to create vivid images of Titan. Notably, two imagers, a visible and an infrared, took 360-degree photos of the Huygen Probe’s surroundings during its 2-hour descent. Combined with a side-view imager and a small lamp that adapted its brightness based on the presence of sunlight, provided us with a relatively accurate image of Titan’s physical appearance.

Lastly, the Surface-Science Package (SSP) was a package that contained multiple sensors designed to collect information about Titan’s surface upon the Huygen Probe’s landing. Notably, an acoustic sensor measured the volatility of the probe’s distance to the ground as it landed the last 100 meters (Volatility would remain low against a solid surface, but fluctuate against ocean waves). The above-mentioned accelerometer measured the probe’s deceleration, which suggested the structure and softness of the surface, while a tilt sensor measured any swinging motion during the Probe’s descent (potentially caused by strong winds).

This collected information was continuously transmitted from the probe to the mother “Cassini”. Despite the short duration of the landing, the “Cassini-Huygens” mission provided scientists with a renewed and sophisticated understanding of Titan’s properties. The mission was considered an overall success, revealing a rich atmosphere, an icy surface, the likelihood of an underground ocean, and, most importantly, sparking the interest of scientists in its resemblance to a very young Earth.

Bibliography (APA)

Barnett, A. (Ed.). (2024, November 3). Cassini. NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/cassini/spacecraft/huygens-probe/

Barnett, A. (Ed.). (2024, November 5). Cassini at Titan. NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/cassini/science/titan/

Barnett, A. (Ed.). (2025, April 25). Titan Facts. NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/saturn/moons/titan/facts/

Brown, M. J. I. (2022, December 7). Why doesn’t the International Space Station run out of air? Australia Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/education/why-the-international-space-station-does-not-run-out-of-air/13928762

Madani, D. (2023, June 28). Astronauts’ urine and sweat are almost entirely recycled into drinking water with new system. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/science/space/astronauts-urine-sweat-almost-entirely-recycled-drinking-water-new-sys-rcna91619

Ridgeway, B. (Ed.). (2025, April 4). Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS). NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/reference/environmental-control-and-life-support-systems-eclss/

US Energy Information Administration. (2023, December 26). Hydrocarbon gas liquids explained. US Energy Information Administration. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/hydrocarbon-gas-liquids/

No AI was used in the writing of this post