Introduction

This assignment serves as the introduction to our larger Planet Exploration project. Our class objective is to identify a planet that could realistically host a vehicle mission, evaluate its potential for human survival, and develop possible solutions for establishing a colony. After reviewing several known exoplanets, our group selected Proxima Centauri b as the most feasible target for this project.

QUick facts

- Distance: 4.24 Light-years (Closest exoplanet to Earth)

- Star Type: Red Dwarf (M-Type Flare Star)

- Mass: Around 1.17 Earths (Minimum)

- Year Length: 11.2 Earth Days

- Gravity: Likely similar to Earth (1.1g – 1.3g)

- Discovery Method: Radial Velocity (The “Wobble” Method)

- Key Feature: Tidally Locked (Permanent Day/Night sides)

Why We Chose Proxima Centauri b

Proxima Centauri b is the closest known exoplanet, orbiting our nearest stellar neighbor just 4.24 light-years away. It’s roughly earth-size and it resides within the habitable zone of its red-dwarf star, meaning it could, under the right conditions, support liquid water. We selected it not just because it is famous, but because it is the only Earth-mass world we found where a vehicle mission is feasible within a human lifetime.

Since Proxima b orbits an M-dwarf star, we get a chance to study habitability around the most common type of star in the galaxy. Although the planet is almost certainly tidally locked, with one hemisphere in perpetual daylight and the other in constant darkness, multiple global-climate models indicate that a sufficiently dense atmosphere or deep ocean could circulate heat efficiently enough to sustain life-supporting temperatures along the twilight boundary. Because of its proximity, the planet is also within reach of realistic near-future probe missions, including laser-sail vehicles that could reach the system within a few decades. All of this makes Proxima b the obvious first choice for interstellar exploration.

Opportunities on the New World

The most interesting feature is probably the terminator zone: a permanent dusk which seperates day and night sides. I found that climate models suggest that if there’s a decent atmosphere, habitability is more likely to be a reality. The zone’s continuous light could power solar systems and support limited agriculture, making it the most stable region for a possible colony.

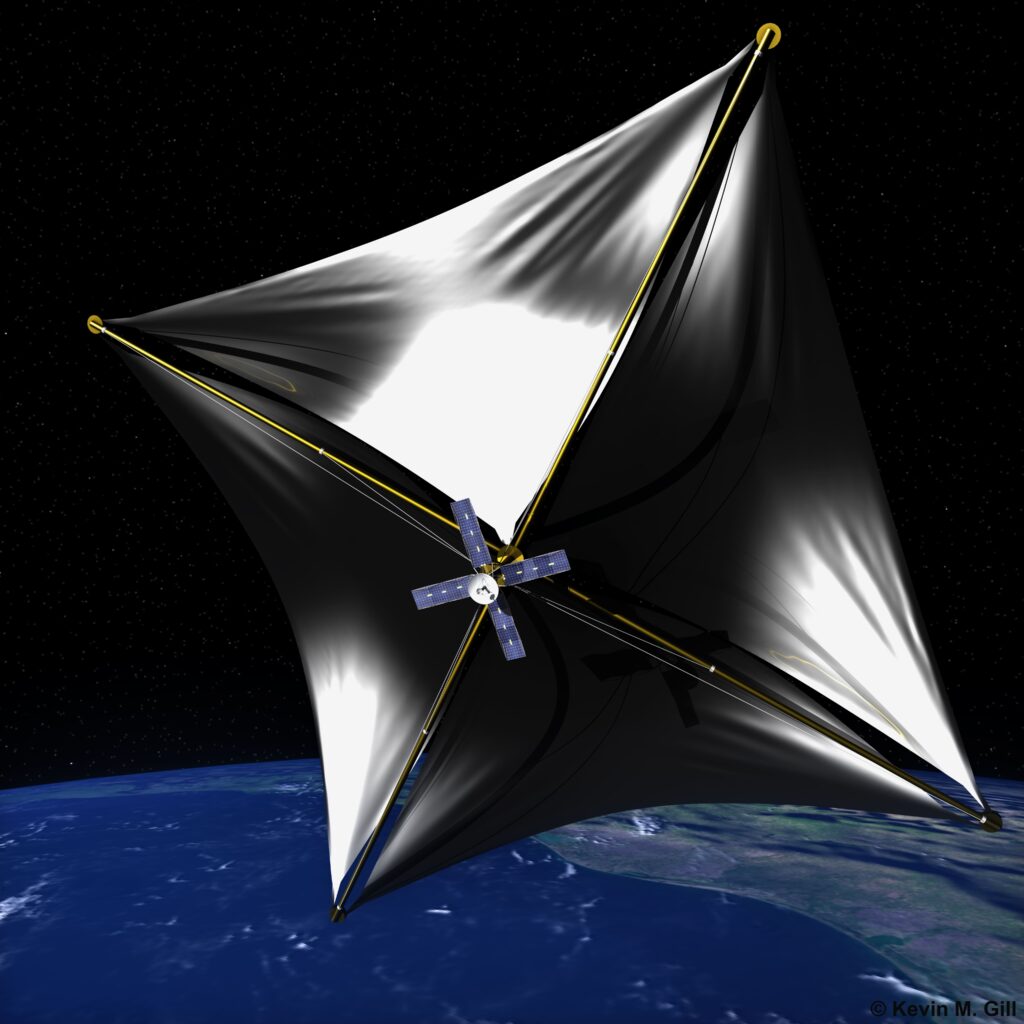

Proxima b also serves as a natural laboratory for studying climates under red-dwarf light. Receiving roughly two-thirds of Earth’s sunlight but in a redder spectrum, it offers insight into how clouds, chemistry, and photosynthesis might function on billions of similar stars. Being so close also makes it perfect for testing for interstellar technology. Once concept we found was Breakthrough Starshot. They proposed tiny light-sail probes traveling much faster than current technology, returning direct imagery and atmospheric data within a human lifetime. We can develop on this concept and hopefully implement it into our trip there.

Breakthrough Starshot: a solar-sail concept

Anticipated Challenges

Proxima b orbits a highly active flare star. Observed “superflares” release ultraviolet and X-ray radiation hundreds of times stronger than Earth’s, capable of destroying ozone and eroding any atmosphere. Over time, this could strip away any atmosphere and leave it barren.

Another obstacle is the lack of direct atmospheric data. Because the planet does not transit its star, we cannot measure its radius or atmospheric composition. Whether an atmosphere even exists (or what surface pressure and temperature prevail) remains unknown. This complicates our vehicle and habitat design by adding more possible variables to deal with.

Next, humans evolved with a 24-hour light/dark cycle. On Proxima b, the sun never sets in the habitable zone. To prevent mental health breakdown and sleep disorders, colony habitats would need ‘artificial horizons’ and shutters to simulate a 24-hour Earth day for the crew and prevent deteriation.

Also, tidal locking seems to add further difficulty. One hemisphere may scorch in daylight while the other freezes in darkness. Without some sort of atmospheric circulation, violent winds and steep temperature contrasts could be detrimental to our mission. This means we have to create advanced thermal systems and colony architecture that is flexible.

Implications for Vehicle and Mission Design

Given these uncertainties, our group decided that a “Swiss army knife” type of strategy is essential.

The first phase would launch interstellar scout probes to gather info. Scouts complete flybys between 10-20 years. During this journey, they can map things like magnetic fields and atmospheric details. This helps us confirm conditions for any future missions. These scouts could complete flybys within 20–30 years. This maps things like magnetic fields and atmospheric details to confirm conditions for future missions.

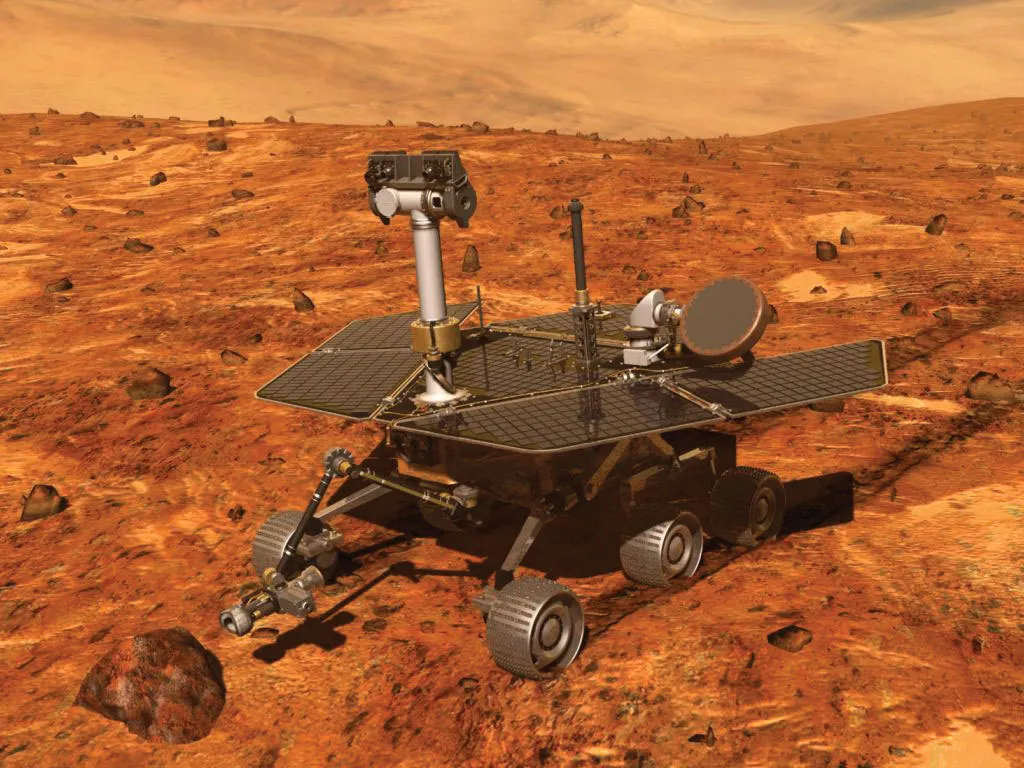

Once we have good data from the first probes, larger and more capable vehicles could be sent to orbit or land on Proxima b. Because we don’t yet know how thick the atmosphere is, these vehicles would need to be flexible. If the planet has a decent atmosphere, they could use a heat shield and thrusters to slow down during entry. If the air is too thin or missing, they would land using engines alone. Landers would also need strong protection from radiation, possibly by using tanks of water around crew areas or digging slightly underground for shelter.

On the surface, future rovers and habitats would have to be tough, sealed, and self-sufficient. Vehicles would be pressurized and protected from radiation and temperature swings between the day and night sides. Settlements would likely be built close to the terminator zone, where conditions are mildest, or placed partly underground for extra insulation and safety. Power would come mainly from small nuclear reactors, since solar energy could be unreliable during flare events, though solar panels could still help when it’s safe to operate them.

Looking further ahead, sending humans to Proxima b is still only a dream. A ship carrying people across interstellar space would have to be enormous, heavily shielded from radiation, and capable of supporting life for decades. NASA’s advanced propulsion studies, such as the Starlight and DEEP-IN programs, are early steps in imagining how this could one day happen. But for now, such missions remain far in the future.

How We Know What We Know

Everything we know about Proxima Centauri b comes from nearly twenty years of telescope data. Still, there are a lot of unknowns. For instance, the image used of Proxima is only an artistic render. We currently have no confirmed representation of how it actually looks. As the planet orbits, it pulls on the star, causing the star to “wobble” in a small circle. This technique is called the radial-velocity method (which we learned about at the Vancouver MacMillan Space Centre).

The physics is straightforward: as a planet orbits its star, gravity works both ways. The planet pulls on the star, causing both to orbit their shared center of mass. This causes a subtle back-and-forth motion. During my resarch, I found that when the star moves toward us, its light becomes more blue. When it moves away, it becomes more red. This is the Doppler effect, the same phenomenon that changes the pitch of a siren as an ambulance passes. The challenge is that Proxima Centauri’s wobble is just over one meter per second, about walking speed, requiring instruments that can measure wavelengths to a precision of about one part in ten million.

In my research, I found exactly who first discovered Proxima b. Between 2000 and 2016, scientists at the European Southern Observatory used HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) on a 3.6-meter telescope in Chile. HARPS splits starlight into wavelengths using a spectrograph, then tracks how absorption lines in the star’s spectrum shift back and forth. The team collected hundreds of measurements over sixteen years, using statistical techniques to separate the planet’s signal from the noise created by the star’s own surface activity.

From that source, I realised we can move forward and go ahead and calculate the wobble speed of the planet. This is important because it is one of the only things we can actually calculate about the planet, which tells us its similarity to Earth. We can calculate the planet’s minimum mass using Kepler’s laws: an object causing a 1.38 m/s wobble in an 11.2-day orbit around a 0.12 solar-mass star must have at least 1.3 times Earth’s mass. The word “minimum” matters because radial velocity only measures motion along our line of sight. In fact, things could be quite different. If the orbit is tilted, the true mass could be even higher than predicted here! In 2020, the ESPRESSO instrument (which is more sensitive) refined the estimate to be about 1.17 Earth masses.

The missing piece is atmospheric data. Most exoplanet atmosphere knowledge comes from watching planets pass in front of their star. During a transit, starlight filters through the atmosphere, and molecules absorb specific wavelengths, creating a chemical fingerprint. As I’ve found online, Proxima b doesn’t transit. Its orbit is tilted so it never crosses the star’s face from our perspective, meaning we can’t measure its radius or analyse its atmosphere. Without a radius, we don’t know if it’s rocky, a water world, or something else entirely.

Howard et al.’s 2018 Evryscope observations showed a different side of things. The Evryscope telescope network caught massive flares in 2016-2017, with one increasing brightness by a factor of 68 and releasing intense UV and X-ray radiation. The Evryscope network uses wide-field cameras to continuously monitor brightness. When the flare occurred, they recorded the star becoming 68 times brighter in visible light. Models suggest this radiation could strip an Earth-like atmosphere over geological time unless a strong magnetic field protects it. Climate simulations show that if an atmosphere exists, even modest pressure could transport enough heat to keep the terminator zone habitable. The Gaia telescope pinned down the distance at 4.2465 light-years with 0.1% precision, which is incredible for our current technology. Gaia measured the distance using parallax. Specifically this meant watching how Proxima Centauri’s position shifts against background stars as Earth orbits the Sun over multiple years.

What we’re left with is a planet defined more by what we don’t know than what we do. We know its mass, orbital period, and distance. We know its star is violent. Models suggest habitability is possible but unconfirmed. Everything else, such as: atmosphere, surface temperature, magnetic field, water, all remains speculation until we send instruments to measure directly.

Behind the Scenes: My Research Journey

I want to be transparent about how I actually built this report, because navigating twenty years of astrophysics data wasn’t easy. My process was a mix of modern AI tools and old-school reading.

Step 1: The “Skeleton” (AI Ideation)

I started with broad Google searches like “Proxima b mission challenges” and “red dwarf habitability.” I used the AI summaries at the top of the search results to build a mental map of the topic. This helped me identify the key keywords I needed, like “tidal locking,” “radial velocity,” and “flare star.” I didn’t use AI to write the content, but I used it as a compass to point me toward the right topics and papers worth looking at.

Step 2: The “Muscle” (Primary Sources)

Once I had the keywords, I switched to Google Scholar to find the actual papers. This was the hardest part. The 2016 Nature paper by Anglada-Escudé was incredibly dense. I honestly didn’t have time to read every single page of every reference. Instead, I used a targeted reading strategy: I read the Abstract to understand the discovery, and then skipped to the Discussion/Conclusion sections where the scientists explain what their data means for habitability. I also used AI to summarise certain parts and explain them to me.

Step 3: The Synthesis

When I got stuck on complex concepts (like how exactly the HARPS spectrograph separates “noise” from “signal”), I would ask an AI to “explain radial velocity noise filtering to a 10th grader.” Once I grasped the concept, I went back to the primary paper to find the specific numbers (like the 1.38 m/s wobble) to ensure my data was accurate and not an AI hallucination. This “sandwich” method (Paper -> AI Explanation -> Back to Paper) ended up allowing me to understand high-level astrophysics that would have otherwise been over my head.

AI Usage

AI was used during the ideation phases of the project, as well as the Google AI search summary (which I cannot retrieve transcripts of) for specific details: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1haFTUZTqk7KVnksyb8deygdtawCaPerfwY02cqDYHH8/edit?usp=sharing

Key References

Anglada-Escudé, G., Amado, P. J., Barnes, J., Berdiñas, Z. M., Butler, R. P., Coleman, G. A. L., de la Cueva, I., Dreizler, S., Endl, M., Giesers, B., Jeffers, S. V., Jenkins, J. S., Jones, H. R. A., Kiraga, M., Kürster, M., López-González, M. J., Marvin, C. J., Morales, N., Morin, J., … Zechmeister, M. (2016). A terrestrial planet candidate in a temperate orbit around Proxima Centauri. Nature, 536(7617), 437–440. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19106

Braam, M., Palmer, P., Decin, L., Mayne, N., Manners, J., & Rugheimer, S. (2025). Earth-like exoplanets in spin–orbit resonances: Climate dynamics, 3D atmospheric chemistry, and observational signatures. The Planetary Science Journal, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3847/PSJ/ad9565

Chen, H., De Luca, P., Hochman, A., & Komacek, T. D. (2025). Effects of transient stellar emissions on planetary climates of tidally locked exo-Earths. The Astronomical Journal, 170(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/add33e

Engelbrecht, N. E., Herbst, K., du Toit Strauss, R., Scherer, K., Light, J., & Moloto, K. D. (2024). On the comprehensive 3D modeling of the radiation environment of Proxima Centauri b: A new constraint on habitability? The Astrophysical Journal, 964, 89. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad2ade

Hammond, T., Komacek, T. D., Kopparapu, R. K., Fauchez, T. J., Mandell, A. M., Wolf, E. T., Kofman, V., Kane, S. R., Johnson, T. M., Desai, A., Arney, G., & Crouse, J. S. (2025). The climates and thermal emission spectra of prime nearby temperate rocky exoplanet targets. The Astrophysical Journal, 984(2), 181. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/adc73b

Howard, W. S., Tilley, M. A., Corbett, H., Youngblood, A., Loyd, R. O. P., Ratzloff, J. K., Law, N. M., Fors, O., Del Ser, D., Shkolnik, E. L., Ziegler, C., Goeke, E. E., Pietraallo, A. D., & Haislip, J. (2018). The first naked-eye superflare detected from Proxima Centauri. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 860(2), L30. https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/aacaf3

Meadows, V. S., Arney, G. N., Schwieterman, E. W., Lustig-Yaeger, J., Lincowski, A. P., Robinson, T., Domagal-Goldman, S. D., Deitrick, R., Barnes, R. K., Fleming, D. P., Luger, R., Driscoll, P. E., Quinn, T. R., & Crisp, D. (2018). The habitability of Proxima Centauri b: Environmental states and observational discriminants. Astrobiology, 18(2), 133–189. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2016.1589

Mota, A., Koch, S., Matthiae, D., Santos, N. C., & Cortesão, M. (2025). How habitable are M-dwarf exoplanets? Modeling surface conditions and exploring the role of melanins in the survival of Aspergillus niger spores under exoplanet-like radiation. Astrobiology, 25(3). https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2024.0023

NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program. (n.d.). Proxima Centauri b. NASA Science – Exoplanet Catalog. Retrieved November 6, 2025, from https://science.nasa.gov/exoplanet-catalog/proxima-centauri-b/

NASA Science Editorial Team. (2017, July 31). An Earth-like atmosphere may not survive Proxima b’s orbit. NASA Science – Exoplanets. https://science.nasa.gov/universe/exoplanets/an-earth-like-atmosphere-may-not-survive-proxima-bs-orbit/

Parkin, K. L. G. (2018). The Breakthrough Starshot system model. Acta Astronautica, 152, 370–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2018.08.035

Peña-Moñino, L., Alvarado-Gómez, J. D., Sanz-Forcada, J., Montesinos, B., Drake, J. J., García, R. A., Salabert, D., & Mathis, S. (2024). Habitability conditions and radio emission of Proxima Centauri b. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 688, A138. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202349042

Turbet, M., Leconte, J., Selsis, F., Bolmont, E., & Forget, F. (2016). The habitability of Proxima Centauri b II: Possible climates and observability. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 596, A112. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201629577

Suárez Mascareño, A., Faria, J. P., Figueira, P., Lovis, C., Damasso, M., González Hernández, J. I., Rebolo, R., Cristiani, S., Pepe, F., Santos, N. C., Silva, A. M., Amate, M., Manescau, A., Pasquini, L., Zapatero Osorio, M. R., Adibekyan, V., Alibert, Y., Allende Prieto, C., Barros, S. C. C., … & Udry, S. (2020). Revisiting Proxima with ESPRESSO. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 639, A77. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202037745

Gaia Collaboration, Vallenari, A., Brown, A. G. A., Prusti, T., de Bruijne, J. H. J., Arenou, F., Babusiaux, C., Biermann, M., Creevey, O. L., Ducourant, C., Evans, D. W., Eyer, L., Guerra, R., Hutton, A., Jordi, C., Klioner, S. A., Lammers, U. L., Lindegren, L., Luri, X., … & Zwitter, T. (2023). Gaia Data Release 3: Summary of the content and survey properties. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 674, A1. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202243940

Leave a Reply to mcrompton Cancel reply