Introduction

Enceladus, the moon of Saturn, presents a challenging yet interesting environment for explorers to explore. It’s one of the many places in our universe where life could potentially exist.

Problem Statement and Approach

My team and I have chosen to design a vehicle to travel safely on Enceladus while avoiding icy temperatures, around – 201 degrees Celsius, maintaining high-power efficiency, avoiding geysers of water vapor, high brightness induced low visibility, dangerous radiation levels, and the possibility of escaping from Enceladus’s gravity pull (0.113m/s2). The vehicle must be able to make a round trip of 10 kilometers.

Our test revolved mainly around mobility and efficiency as they are key factors to having a safe round trip. Check out more of the test planning at this post: https://wp.stgeorges.bc.ca/joshuac/2024/11/30/designing-a-vehicle-for-enceladus/

Final Design and Prototype

CAD Designs of the Full Vehicle

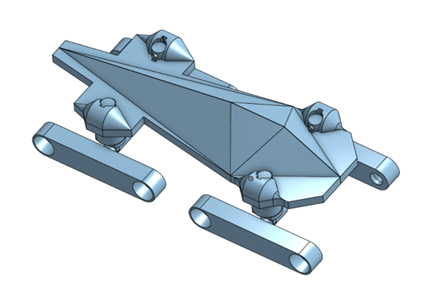

Our CAD design was changed greatly during the process due to multiple failed printing processes.

What started like this

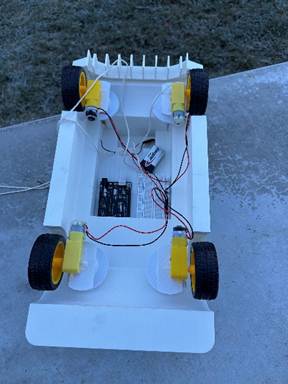

Ended up like this

Building the vehicle

The outline and basic model were printed through multiple trials and errors. Originally, we aimed to add suspension to each of the 4 wheels, however, we were running out of time and couldn’t properly fit the suspension in. The motors and wiring all came from an Arduino kit. With a 9-volt battery, we attached a string to pull out the wire to stop the vehicle.

Our team encountered a lot of problems during the wiring process. Some motors would not receive enough power, spin the wrong way, or spin at different speeds. The end solution to that problem was to use a 9-volt battery and make the wiring a lot simpler.

Testing Process

Test Setup

The testing environment included an indoor controlled environment as well as bumpy and slippery terrain outdoors.

The indoor testing environment was on the cement floor, room temperature at around 20 degrees Celsius

The outdoor testing environment required the use of a tarp, gravel, and water spray to set up terrain. The temperature was around 2 degrees Celsius.

Control Variables

Battery 1: Starting voltage – 9.55 volts

Battery 2: Starting voltage – 9.00 vots

Test Execution

Test 1: Control

During the first test, the vehicle was placed on the cement ground as a control variable and to test its basic functionality. The vehicle travelled 293cm each trial. We conducted three trials and measured the final voltage of the battery after.

Battery 1 ending voltage – 9.00 volts.

Distance – 293 cm * 3 = 879 cm

The test can be viewed at: https://youtu.be/15-6Gy0pEwg

Test 2: mobility

The second test was the main test for mobility. With the brumby, slippery, and cold terrain simulated for Enceladus the vehicle struggled and could not cross the terrain at all. In the video you can see that when even one of the wheels wasn’t touching the ground, the vehicle could not move on its own. The test demonstrated the vehicle’s lack of power and lack of mobility.

The test can be viewed at: https://youtu.be/M7K3Gr8lNkk

Test 3: efficiency

With the second test ending in a massive failure, we still needed to test for efficiency. We figured that there most certainly is a difference in the rougher and colder outdoors compared to the indoor test. So, we created a third test to ensure we still gained helpful data. We ran the vehicle for 293 cm and for three trials then proceeded to measure the battery voltage after.

Battery 2 ending voltage – 7.95 volts

Distance – 293 cm * 3 = 879 cm

The test can be viewed at: https://youtu.be/5OLabCwu3cg

Data Collection

The data collected from the test included navigation efficiency, energy consumption, and drill effectiveness. The following graphs illustrate the key data points:

Efficiency:

| Starting Voltage | Ending Voltage | Voltage Change | |

| Test 1 | 9.55 | 9.00 | 0.55 |

| Test 3 | 9.00 | 7.95 | 1.05 |

The difference between the two tests demonstrated how the outdoor environment drastically changed the energy required for the vehicle to perform the same task. The two most obvious factors include the cold and the bumpy terrain.

We compare the Efficiency of the two tests with the following equation:

Efficiency(%)=(Energy Input/Energy Output)×100

Since we only know the voltage drops we can calculate the ratio of voltage drops:

(Voltage Drop in Test 1/ Voltage Drop in Test 2)x100

(0.55/1.05)x 100 = 52.38%

Test 1 consumed less energy than test 2. The voltage ratio implies that Test 1 was around 52% more voltage efficient compared to Test 2. A lower number would mean less energy was used to complete the test, this compares how much energy was conserved in Test 1 relative to Test 2. With more data we can calculate the power consumption of the two tests.

Mobility:

Test 2 proved that our current prototype had no mobility, and it also lacked power. During the test, even though 3 of the wheels were on the ground spinning, the vehicle could not move. This proved that the individual wheels lack the power needed to move the vehicle through difficult terrain. The 9 volt battery was probably not sufficient in power.

Conclusions and Improvements

Conclusions

The test results demonstrated the need for improvements if we want the vehicle to operate efficiently on the moon, Enceladus. Although we’ve been able to make the vehicle function, the harsh circumstances on the moon will render the vehicle incapable of transporting objects or people.

Design Improvements

Based on the test data, there are two major design improvements that we need to make.

Firstly, the vehicle needs better Insulation to protect it’s power source from the extreme cold. If the power source already experienced a 52% drop in efficiency at 2 degrees C, there is no way it can handel Encleadus’ tempeature at -198 degrees C. One way to achieve insulation is through creating vacuum chambers around the power source. This will prevent heat loss through conduction or convection.

By creating two layers of insulation with a vaccum chamber in between, we can minimize the heat loss. With the use of pumps, the air inside of the chamber can be removed before deployment. The vehicle can access the power source while mainting the airtight seal through the use of ceramic seals. These seals prevent air leaks while still providing electricity feedthroughs.

Secondly, our mobility test has proved that there needs to be major change in the vehicles wheels as well as how it navigates the tough terrain. We can improve this design by incorporating suspension into the vehicle. By using an independent suspension system and delivering more power to each wheel the vehicle can move even when one of the wheels isn’t in contact with the surface.

Furthermore, with the use of spike wheels, the slippery terrian of Enceladus can maintain traction on the ice. This will improve it’s mobility and prevent the vehicle from slipping.

Implications for Future Exploration

Our prototype is a much smaller version of what we would need to transport people. An actual verison would require the additional design improvements as well as space for a crew and storage.

Enceladus holds many secrets that are yet to be descovered, perhaps this prototype is a step in the direction of finding another home for humanity. Beetlejuice out.

Usage of AI

The usage of AI is fully transcribed on this document https://docs.google.com/document/d/1v3L053WAT_JyN3BO0b0ua8tVCwaFNa4vFYJKBg9iVH0/edit?usp=sharing

Leave a Reply